Climate change then and now

The world that the Tsiigehtchic steppe bison lived in 13,000 years ago was one of tremendous change as the Earth’s climate warmed. This brought to a close a glacial period that had lasted for more than 85,000 years.

Today, the Earth’s climate is warming again. Permafrost and ground ice, some of which have survived from the last glacial period, are thawing leading to catastrophic erosion of northern environments.

The steppe bison died off during the first warming and was revealed 13,650 years later during the current period of rapid global warming. What can the steppe bison teach about the worlds it existed in, as a living animal and as a fossil, over 13,000 years apart?

Almost all of Canada was covered by thick sheets of ice 20,000 years ago. These were the continental glaciers, with thick ice masses similar to those we see today in Greenland and Antarctica.

The Laurentide Ice Sheet covered the Canadian north and butted up against the eastern slopes of the Richardson and Mackenzie Mountains in the Northwest Territories.

Fossils of steppe bison and other ice age mammals are rare from the Northwest Territories because most of this region was covered by glaciers during the ice age.

Around 15,000 years ago, global climate began to warm and glaciers melted. As the glaciers retreated eastward across northern Canada, new habitats opened up for ice age mammals. Woolly mammoths, horses and steppe bison migrated from Yukon to the Mackenzie River valley and into the Northwest Territories.

Thanks to Shane Van Loon’s discovery in a thaw slump, we now have this incredible steppe bison from Tsiigehtchic.

What is a thaw slump?

Active thaw slumps contain a headwall of ice-rich permafrost, an area of lower slope where thawed materials accumulate, and a debris tongue that develops as sediments flow downslope. Thaw slumps grow upslope when icy permafrost exposed in the headwall of the slump thaws in summer.

Headwall of a thaw slump in the Peel Plateau, NWT.

What is a thaw slump?

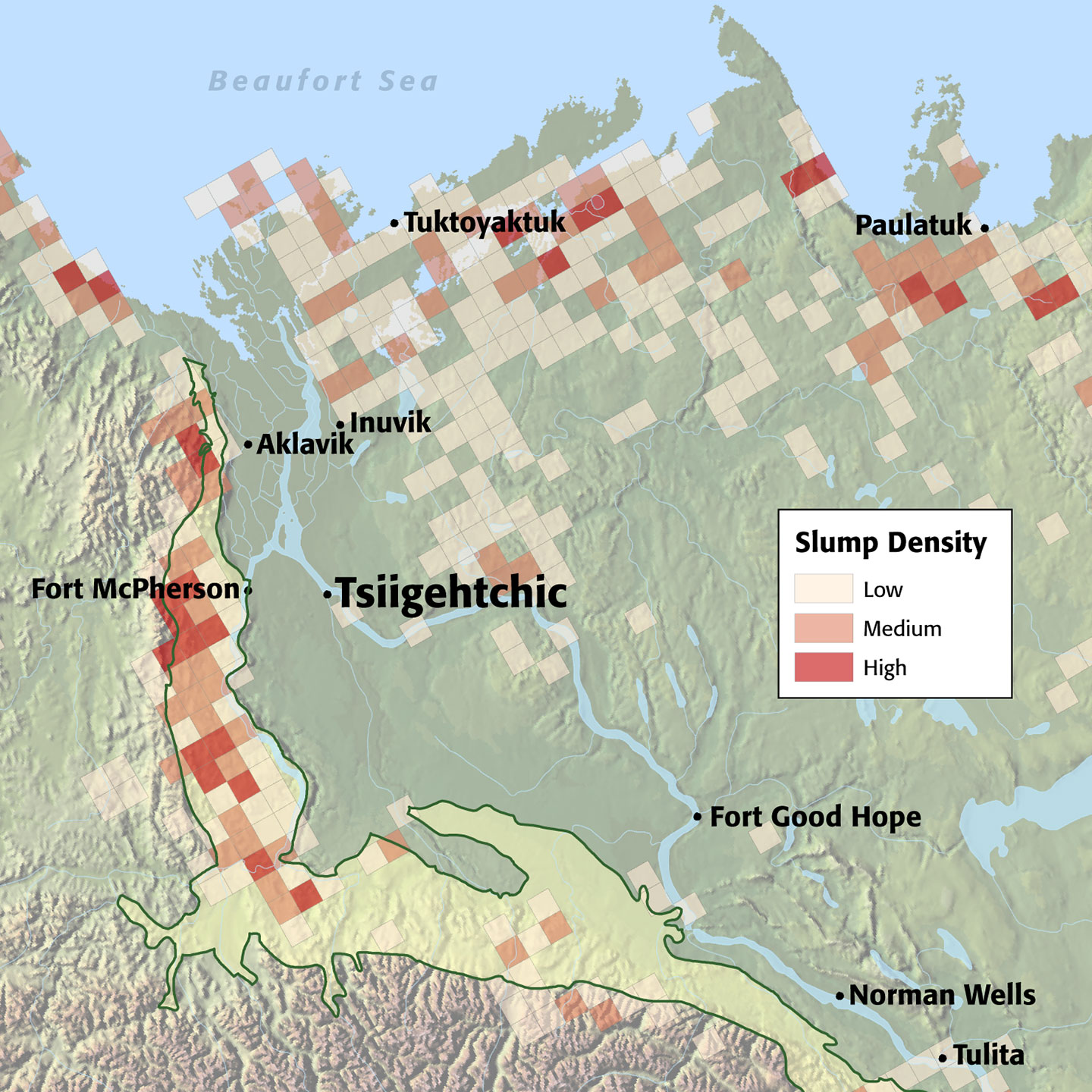

Large slumps are serious hazards that can impact roads, traditional travel routes and land uses. They can pose a hazard to wildlife which can become trapped in the mudflows downslope of the slump headwall. Over the past few decades some of the largest slumps in the Peel Plateau have grown to exceed 30 hectares (37 Canadian football fields) in area. A large thaw slump can displace more than one million cubic metres (600,000 pickup truck loads) of sediment downslope into stream valleys, lakes or coastal areas.

A warmer and wetter climate is causing larger, longer-lived slumps to develop in the NWT. The growth of these disturbances will accelerate with continued climate warming.