Ancient Creatures, Ancient Stories

Deetrı̀n’ Ehchı̨ı̨ K’ı̀t • Raven’s Beds

The steppe bison remains were found near three distinct hollows in the bank of the Arctic Red River. To the Gwichya Gwich’in, these depressions are known asDeetrı̀n’ Ehchı̨ı̨ K’ı̀t, which translates as “Raven’s Beds.” Gwich’in stories about Raven come from a time when animals and humans could change their forms and talk to each other. They reveal Raven as a complex character – known for his magical powers and keen wit as much as for his vanity and ability to deceive.

In one of these stories, Raven, fuelled by his vanity, sets out to trick the grebes (diving waterbirds) into losing their beauty. While Raven is able to trick the grebes into singeing their beautiful feathers, he is caught by the grebes, horribly burned, and loses his beak.Deetrı̀n’ Ehchı̨ı̨ K’ı̀t is the place that Raven recovers from his wounds and plots how to get his beak back.

Listen to the Gwich’in legend of the Raven’s Beds, a traditional story originally told by Annie Norbert and voiced by Alestine Andre (English) and Karen Mitchell (Gwich'in).

The Mammoth and the Mouse

In another Gwich’in story from the time of Raven, a mammoth appears as an important character. In this story, a young man seeks advice from his father-in-law on where to find the materials to make arrows. The father-in-law, who is secretly planning the demise of the young man, sends him to the land of the great beasts to find bones for making arrowheads.

Faced with killing a mammoth, the young man asks a mouse for help, saying, “Little mouse, you run up that big animal’s back leg. Go in his rectum and chew along his spinal cord till you come to the main heart vein. You will get lots of food.”

The little mouse does this and kills the mammoth. To this day, you can still see tiny mouse tracks on the backbones of big animals.

After facing more challenges to collect arrow shafts and feathers, the young man makes an arrow and uses it to kill the evil father-in-law.

Atachuukąįį

Along with the Gwich’in, many other Dene tell stories of a distant time when giant beavers inhabited the landscape. These beavers were a great danger to the Dene, often using their giant tails to splash the water and upset canoes.

Atachuukąįį, a Dene culture hero, chased and killed the giant beavers in order to make the world safe for humans. Many landscape features in the NWT were formed byAtachuukąįį’s struggle against the giant beavers, and today are marked by place names that memorialize these events. Ice age fossils of giant beavers tell us that they were as big as black bears and had incisors (front teeth) that were more than 15 cm long. Along with mastodons, mammoths, and many other ice age species, giant beavers went extinct around 10,000 years ago.

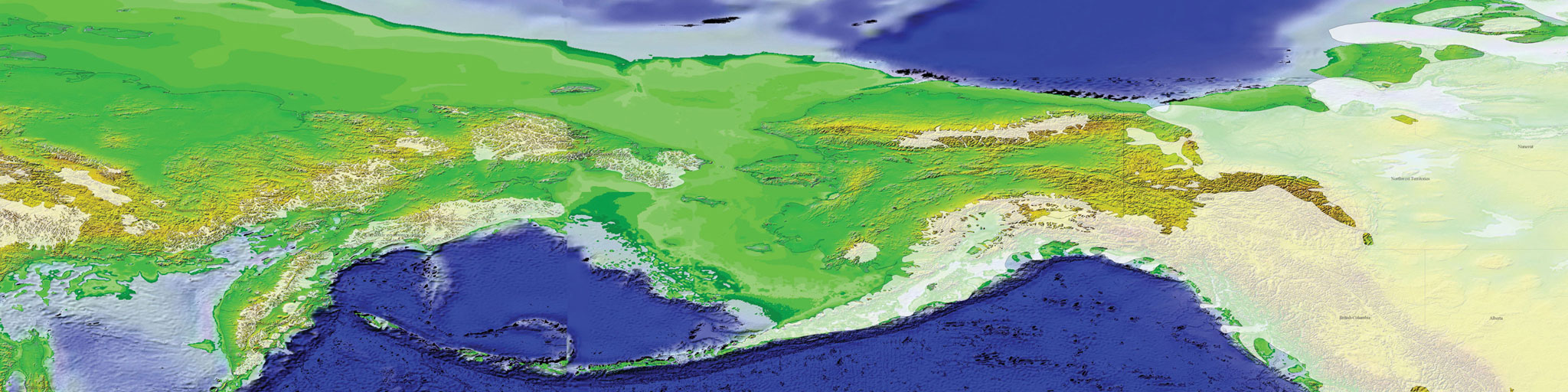

Beringia

During the last glacial period, enough of the Earth’s water became frozen in the great ice sheets covering North America and Eurasia to cause a significant drop in sea levels. This exposed the sea floors of the continental shelf of eastern Asia and western North America, linking the continents with a massive land bridge, called Beringia. About 15,000 years ago, water from melting ice flooded the seas and created the Bering Strait. The coastlines assumed their present shape about 6,000 years ago.

The ice-free landscape of Beringia was a refuge for tundra plants and animals that could survive its windswept Arctic desert conditions. The Tsiigehtchic steppe bison lived at the very eastern edge of Beringia. This indicates that even near the edge of the ice sheets, the local ecology was rich enough to support herbivores such as bison. Humans also lived in Beringia and archaeological sites in Siberia, Alaska, and the Yukon preserve evidence of their hunting and other activities.

Mammoth Steppe

Steppe bison lived in an ecosystem that no longer exists in the north today. Instead of the boreal forest or tundra, ice age Beringia was a vast grassland, or steppe. Woolly mammoths, camels, horses, and bison thrived in this landscape. Their remains were often well preserved in permafrost soils, leading scientists to call Beringia ‘an ice age genetic museum.’

The relationship between steppe vegetation and large ice age mammals has lead scientists to call this environment the Mammoth Steppe. The climates of Beringia were very dry and windy, leading to dusty conditions in summer, with a mix of exposed ground and snow drifts in winter. There were few trees or lakes, but in summer the grassland vegetation was diverse, and included shrubs and a rainbow of coloured wild tundra flowers. The three most common large animals were bison, horses, and mammoths, all grazers adapted to eating grass.

Extinction

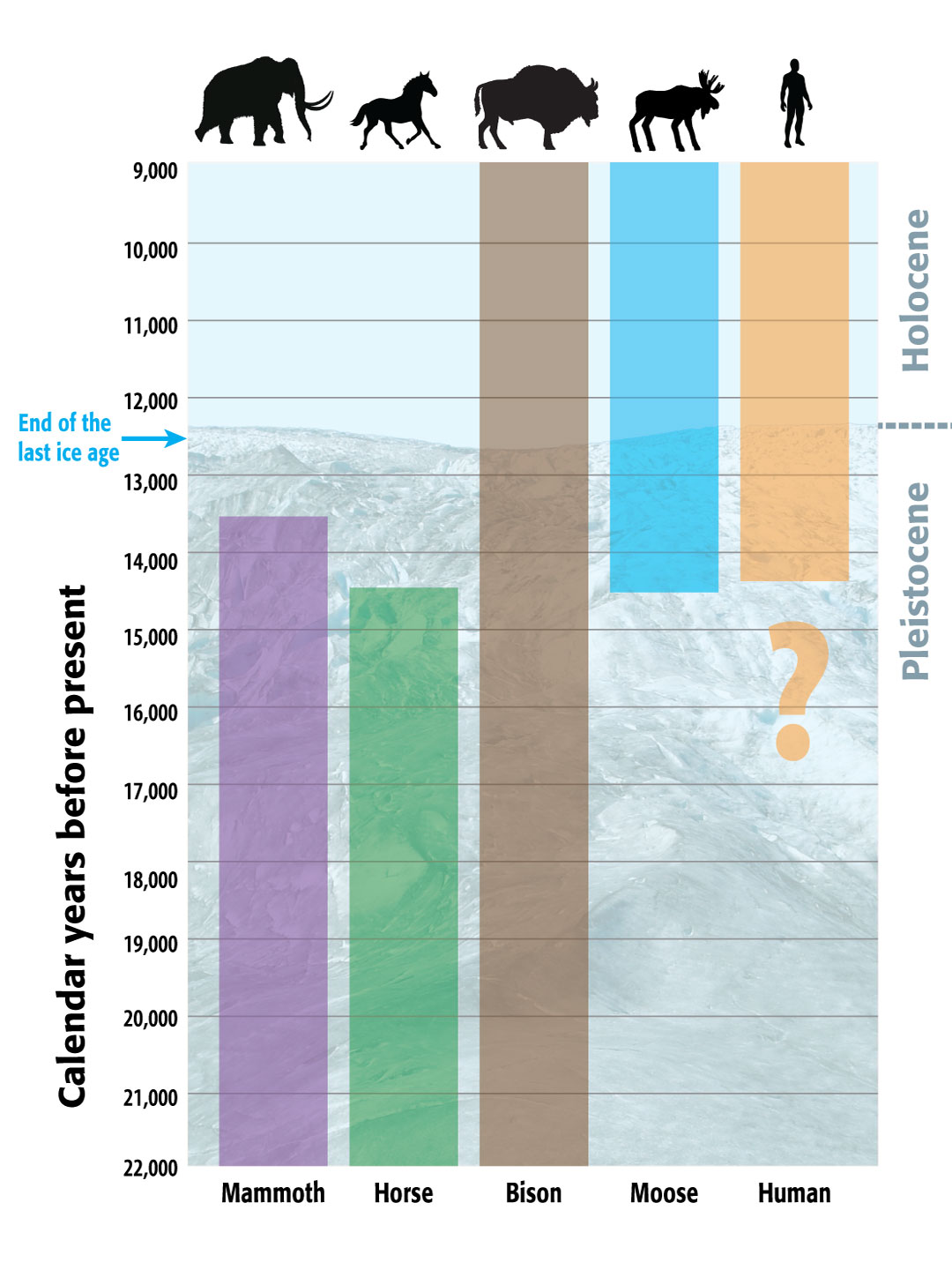

The warming temperatures that marked the end of the ice age led to worldwide ecosystem change and the extinction of many animals of the Mammoth Steppe.

Some have suggested that 70% of all animals weighing more than 40 kg became extinct.

In North America, many species became extinct, including all species of horse, camel, and sloth. Woolly mammoths, mastodons, American lions and giant beavers also disappeared. However, some species like the bison and beaver, survived in North America in smaller forms.

When climates warmed at the end of the ice age, the ground became wetter and the Mammoth Steppe was replaced by the shrub tundra and forests we know today. The warmer environment became much more hospitable to animals that are common now, like caribou.

With these changes and extinctions in the north came new opportunities for other animals such as elk and moose who first crossed the Bering Land Bridge into North America around this time. Herds of caribou and muskoxen followed the retreat of the glacier ice across the North American Arctic and into Greenland.

The end of the ice age brought many changes including the extinction of most large mammals. However some, like the bison, survived by evolving to meet changing conditions. Changing environments created new opportunities for other species, like moose and humans, leading to their migration into North America.