How to use this website

See below for instructions on how to navigate the virtual exhibit.

| Use the tab at the top of the screen to access the site index. | |

| Swipe the panels, or use the tabs at the top left/right sides of the screen to flip between the previous or next slide. | |

| Touch the images to enlarge. A button on the top-right will close the image and return you to the slide. |

What is an ice patch?

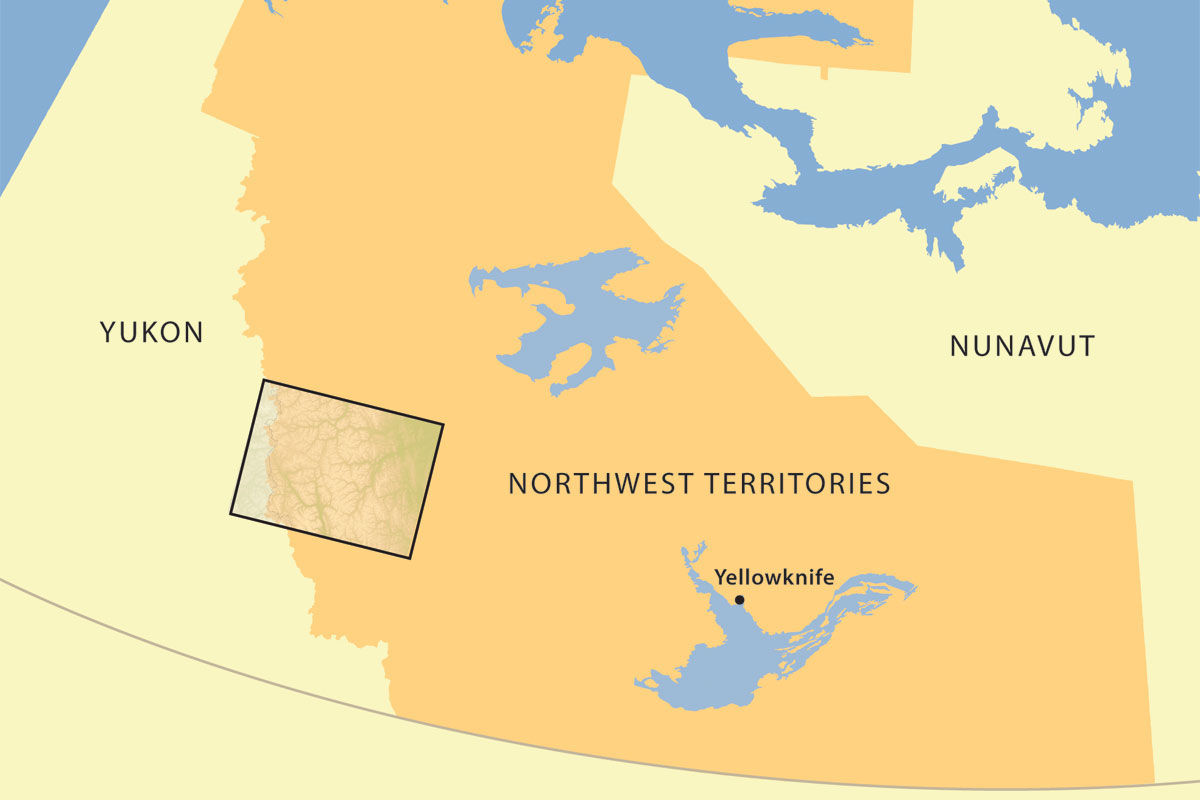

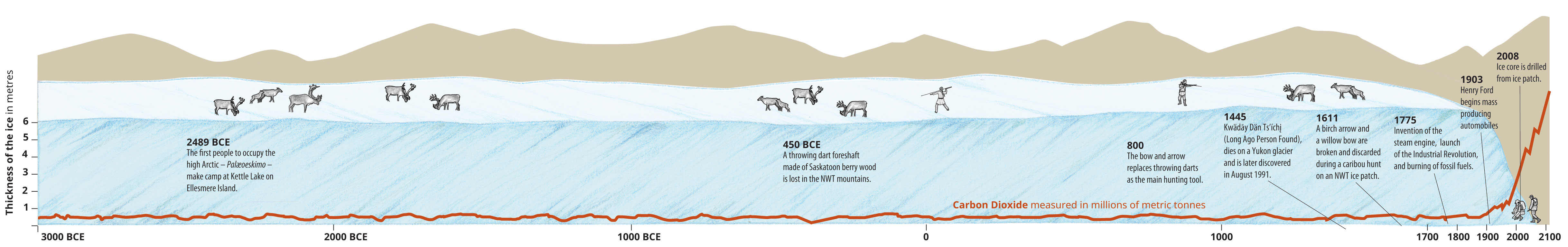

Alpine ice patches are formed from snow that falls on north-facing sides of mountains in the winter. Protected from the sun, these annual layers of snow do not melt away entirely during the summer. Each year new snow is added and, as the patch grows, it begins to compress into a permanent ice layer. Ice patches are located at elevations higher than 1500 metres. They range in size from a few metres to over a kilometre long, and can be up to five metres thick. Some ice patches in the Selwyn Mountains of the Northwest Territories have existed for over 5000 years.

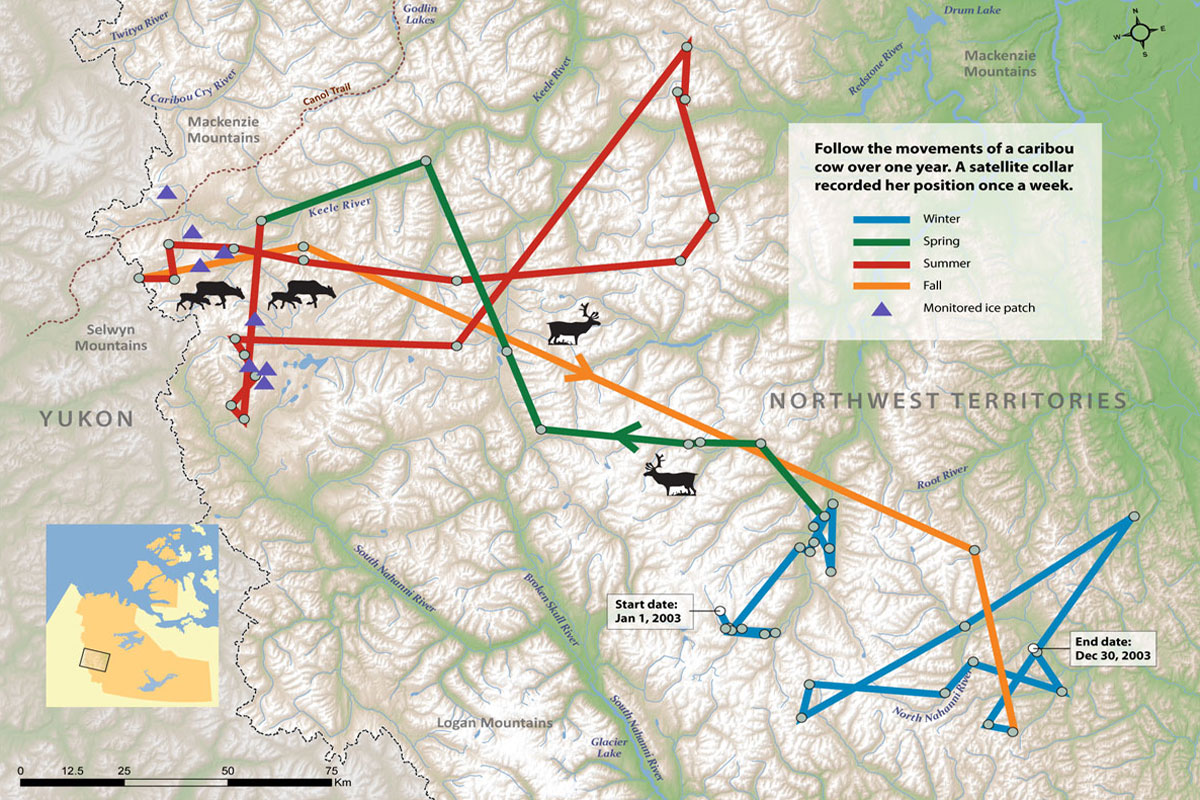

Ice patches are important habitat for caribou in the summer months. They provide a place for caribou to keep cool and seek relief from swarms of biting insects on hot summer days. Over the summer, caribou dung builds up on the surface of the ice patch, and this dung becomes trapped in the ice as the patch grows.

Why do we study them?

Thousands of years ago hunters began making trips in summer to hunt caribou on ice patches. Sometimes these hunters would lose a piece of hunting equipment. Frozen in ice, even the most fragile pieces of these artifacts are preserved, including wood arrow shafts, sinew binding, and the feathers used to fletch arrows.

Ice patches are actively melting as the global climate warms, revealing well-preserved archaeological artifacts and biological specimens. Studying the artifacts from ice patches sheds light on how people lived in the mountains. Biological samples collected from ice patches, such as caribou dung and bones, provide exciting opportunities to study changes in mountain caribou ecology over the past 5000 years.

Hunting caribou

on the ice patch

Mountain Woodland Caribou

The caribou that live in the Selwyn and Mackenzie Mountains belong to the Redstone population of mountain woodland caribou, which may number as many as 5000 to 10,000 animals. They spend the winter months in the lower elevation front ranges of the Mackenzie Mountains, where snow is shallow enough that they can dig down through it to find lichens to eat.

In the spring, the caribou begin to migrate more than 100 kilometres, climbing up to the calving grounds near the NWT/Yukon border. The calves are born between mid-May and mid-June. The caribou spend the summer months in this area. Alpine ice patches are an important part of this summer habitat.

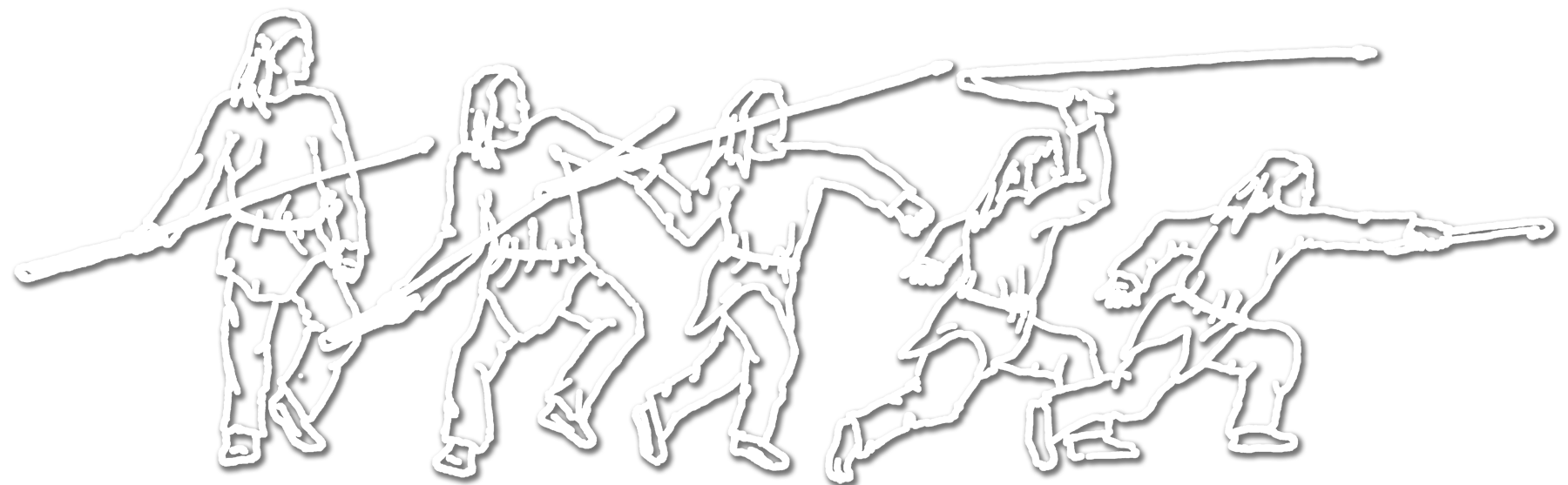

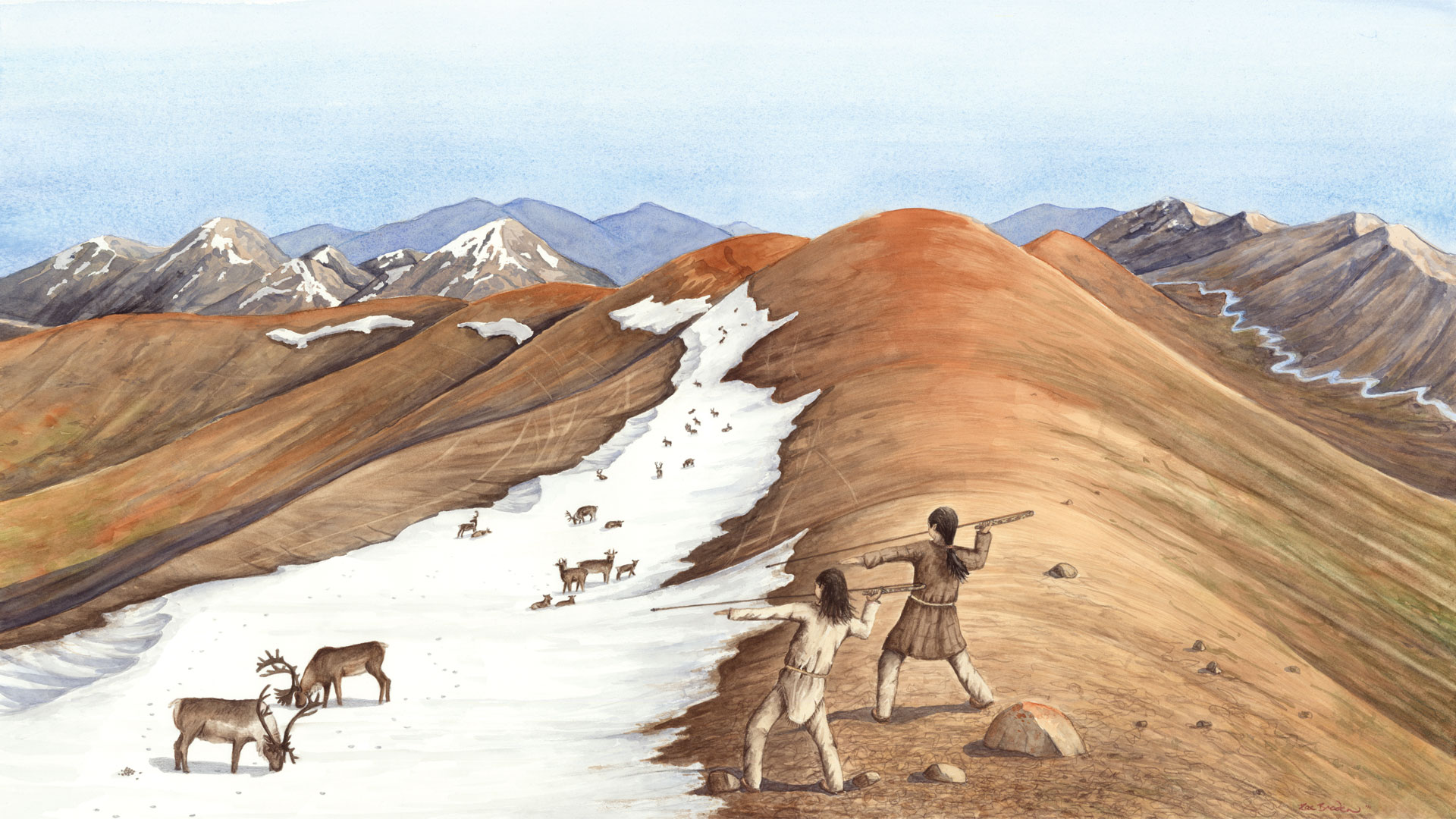

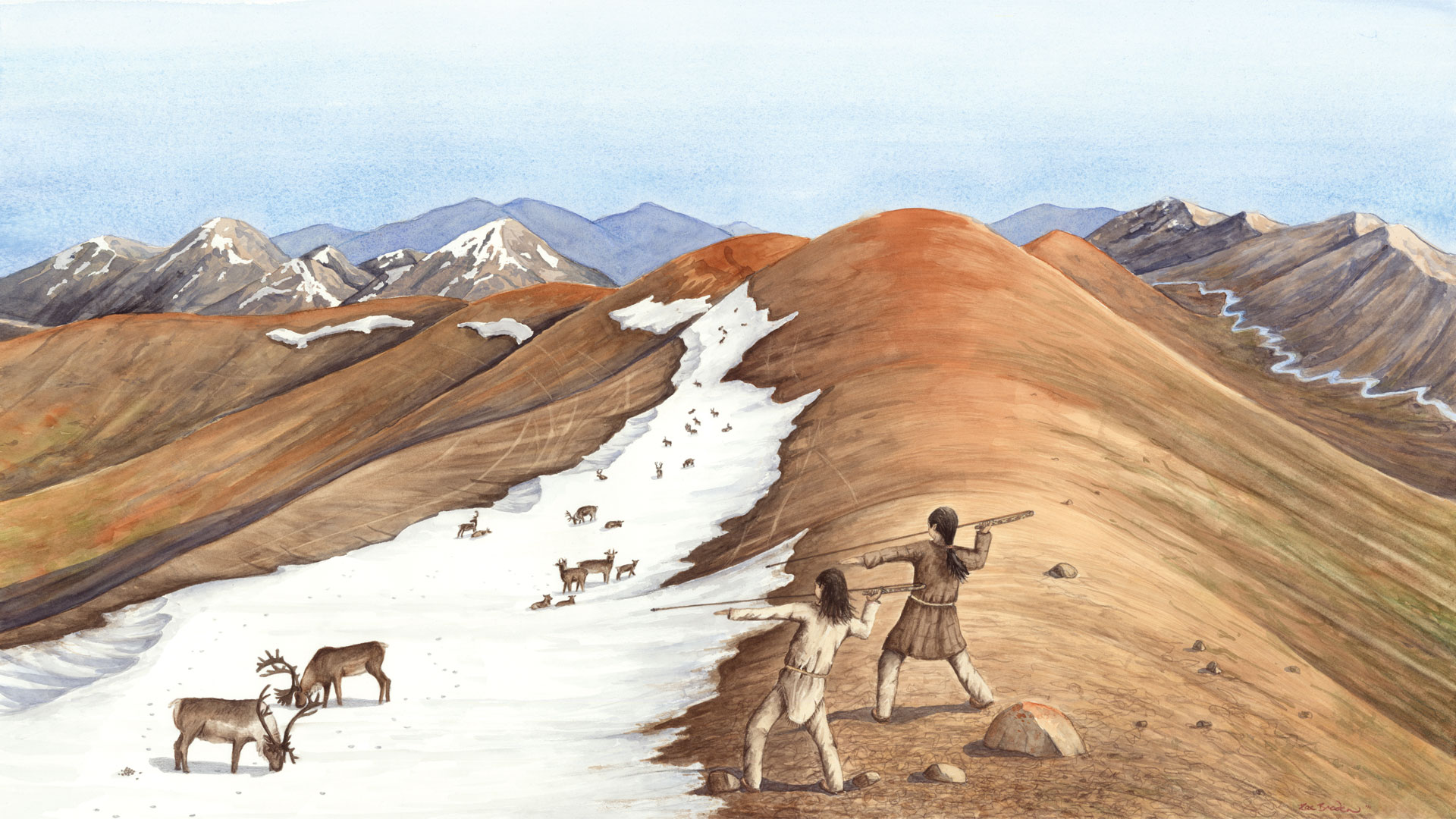

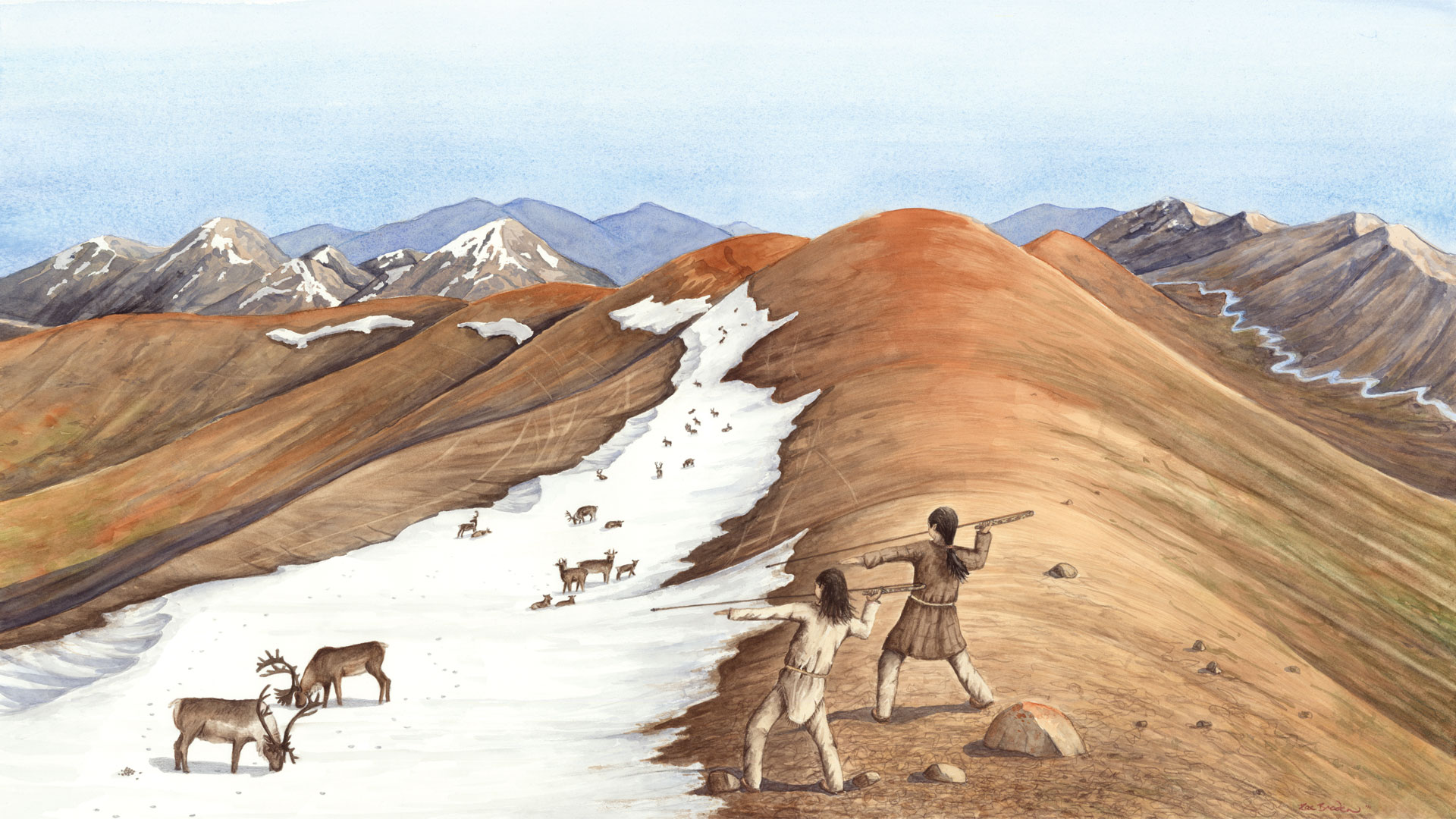

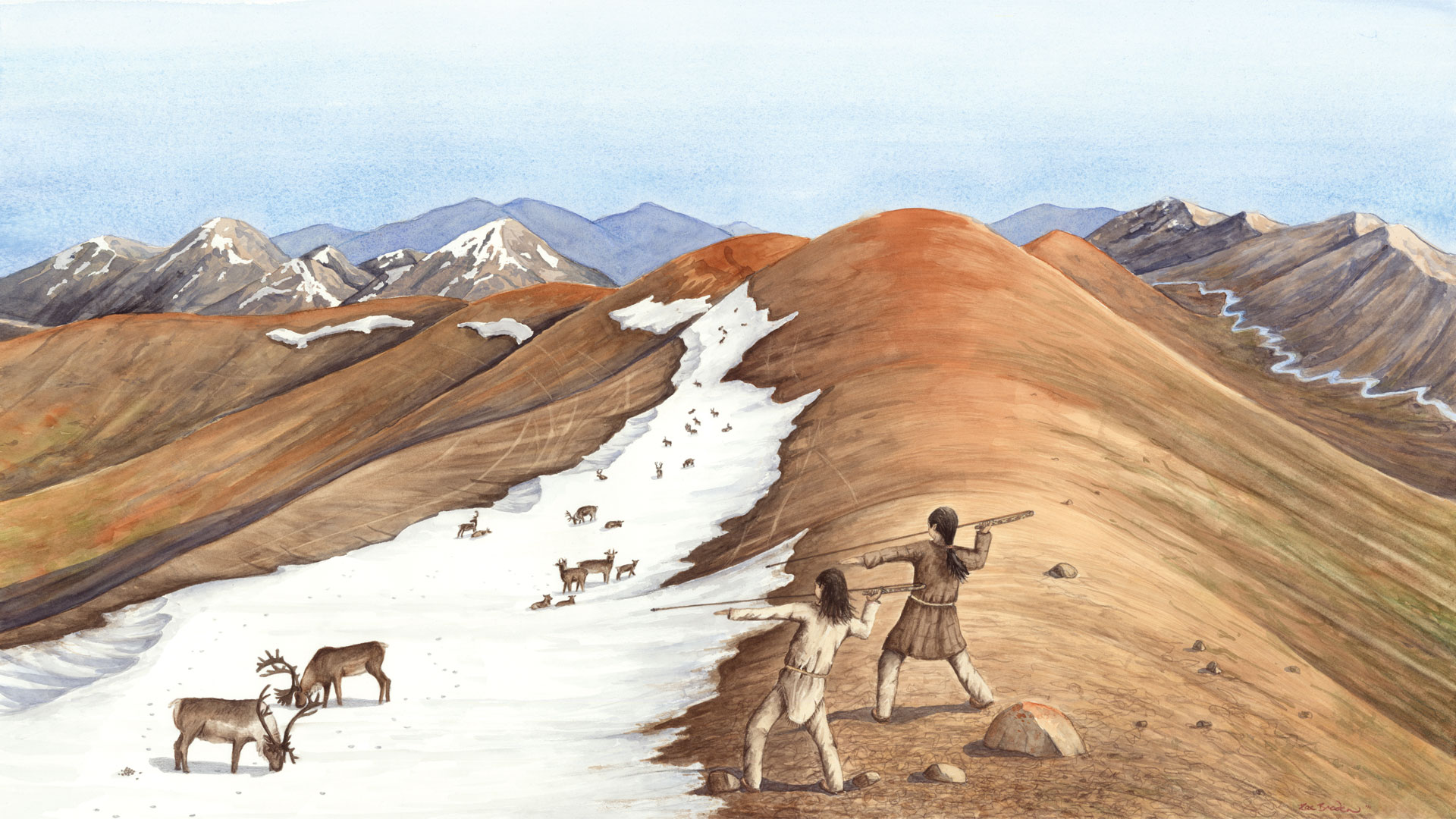

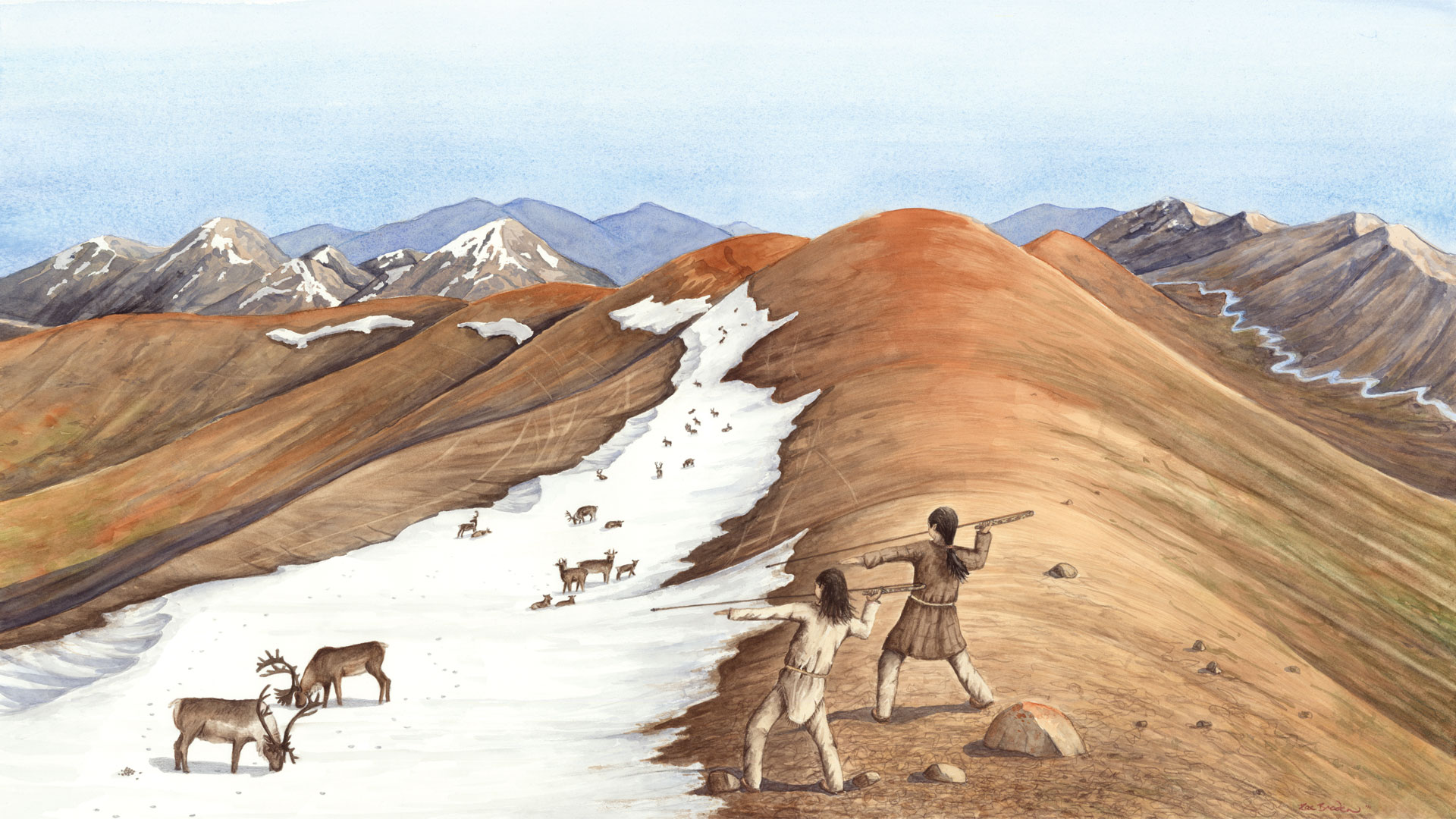

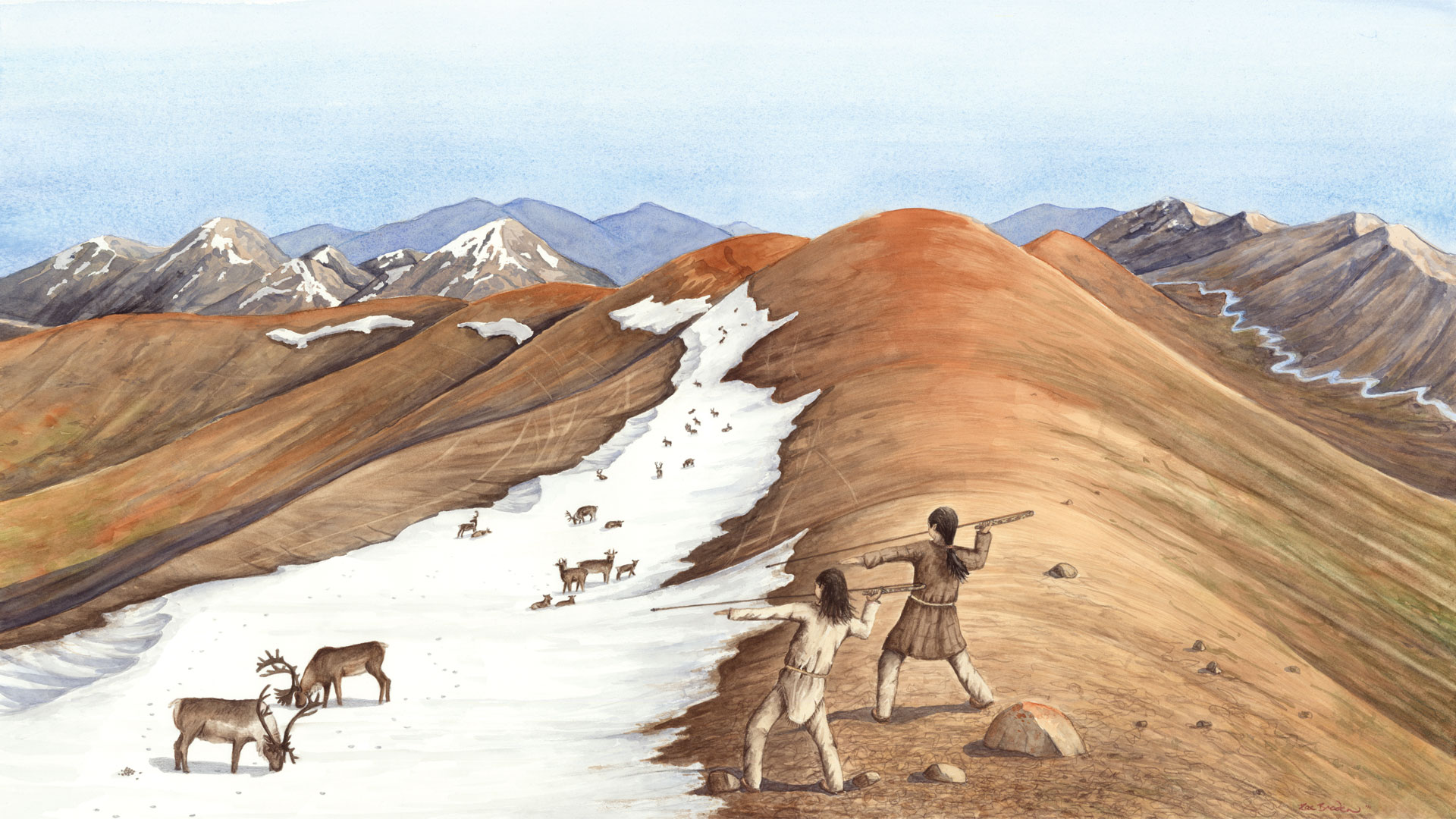

Story of Two Hunters

The two Shúhtagot’ine hunters portrayed in the background artwork, left their camp at Túoch’ee Tuwé (O’Grady Lake) early in the morning. They crossed K’atieh (willow flats) heading for the zhaayáfelah (ice patch). They knew that as the day warmed ɂepę́ (caribou) would begin to gather on the ice patch to cool off in the zha (snow) and to escape įnįįgu (warble flies).

The hunters climbed unseen up the south-facing side of the mountain and moved quickly over the crest. They ran to within 30 metres of the caribou, close enough to kill their surprised prey with throwing darts.

The ice patch portrayed here is known today by archaeologists as KfTe-1. It is located near the NWT/Yukon border in the Selwyn Mountains at an elevation of 1950 m (6400 ft). The scene recreates a hunting event from 2461 years ago.

The Shúhtagot’ine

The Shúhtagot’ine, "people of the mountains", have lived and hunted in the alpine area straddling the Mackenzie and Selwyn Mountains for more than 5000 years.

Today, in the Northwest Territories, the Shúhtagot’ine live principally in the community of Tulita. As part of the NWT Ice Patch Study, elders helped explain how ice patches were used in the past. This information was critical in helping to find ice patches and to help explain what we found at them.

We found hunting tools along the edges of receding ice

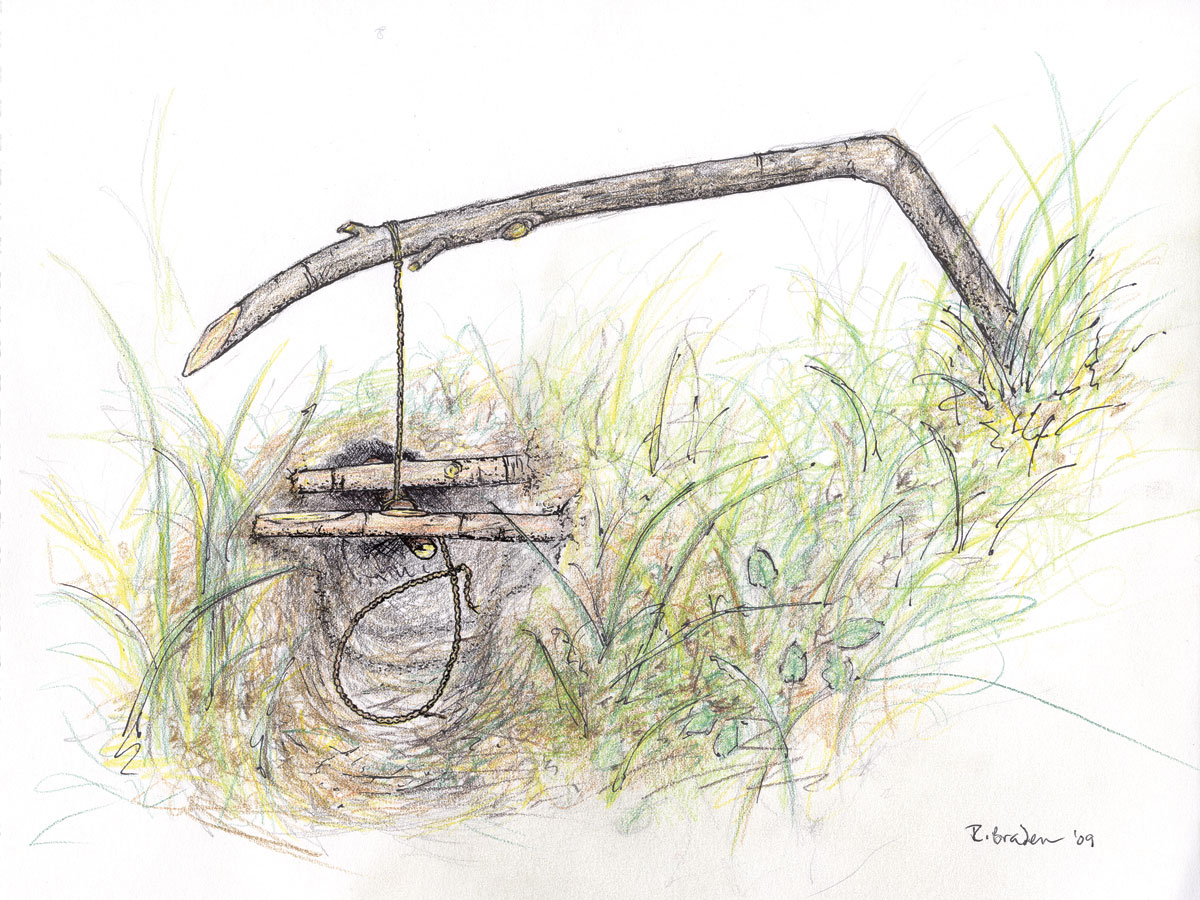

Ground Squirrel Snare

The Shúhtagot’ine have used snares for thousands of years to catch everything from hares to moose. Larger animals would be caught using a snare made from several strands of babiche (raw hide) braided into a strong rope. Smaller animals, such as hares and grounds squirrels, would be caught using snares made from just a few strands of sinew or babiche. Ground squirrels were an important source of food and their hides were sewn into beautiful cloaks. Hunters snared them while waiting for caribou.

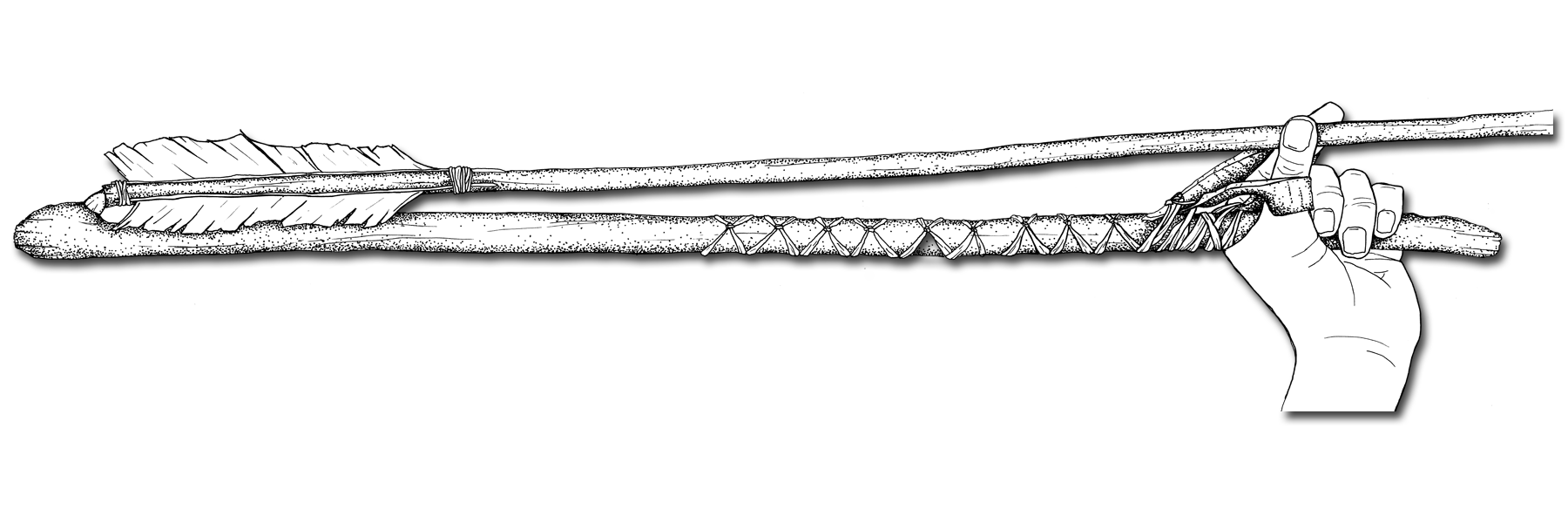

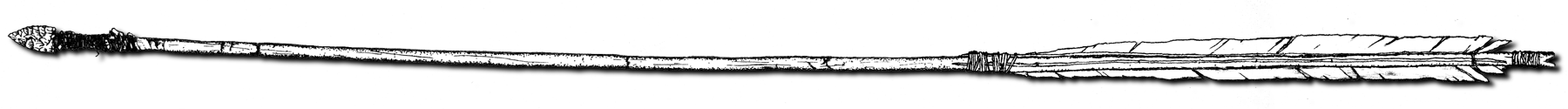

Bow and Arrow

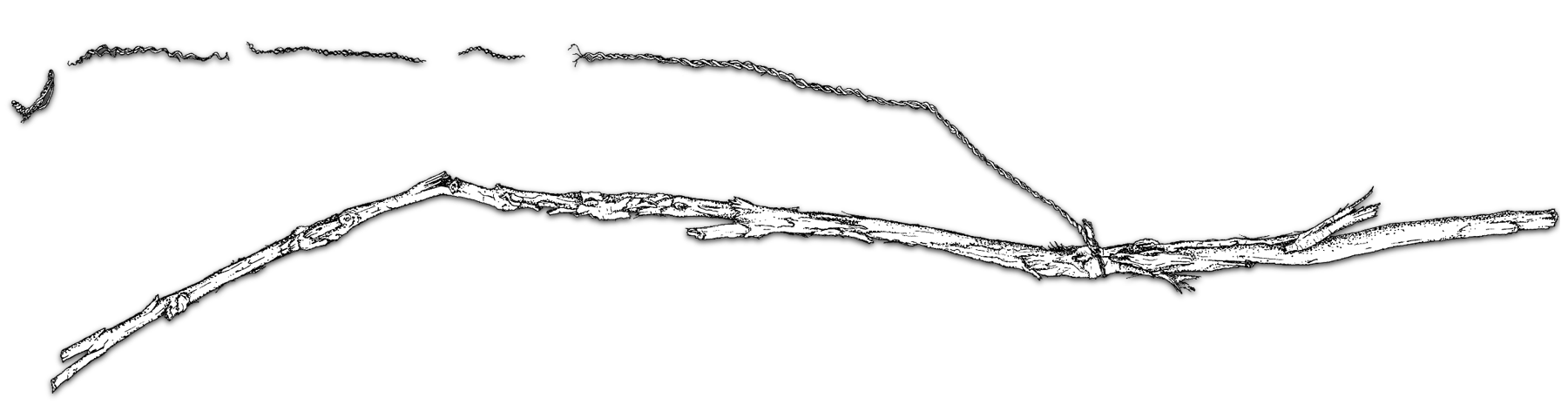

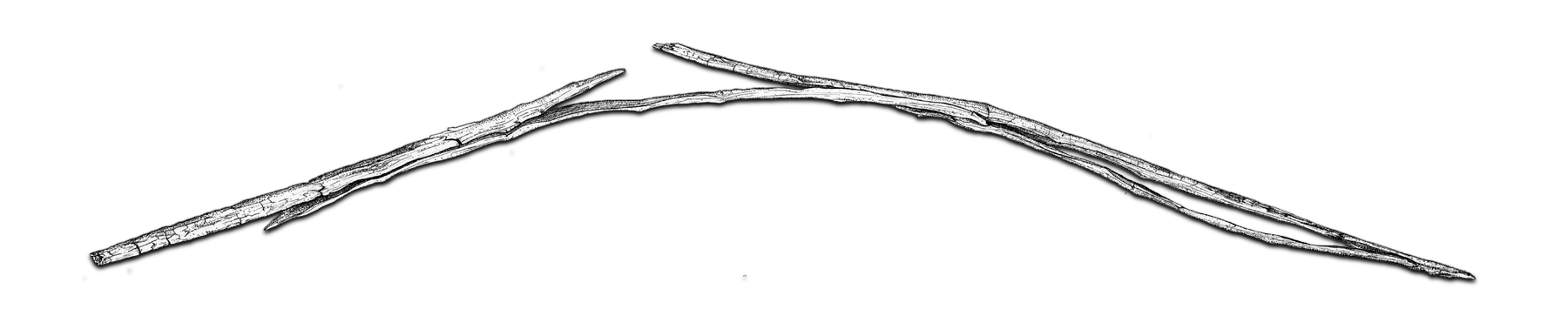

The bow and arrow was one weapon used to hunt caribou on ice patches. More than 400 years ago, a hunter broke his bow while hunting on an ice patch. This bow was found in 14 pieces that had to be put back together like a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle.

The second drawing below shows an arrow that melted out of an ice patch. This arrow has a stone point attached to a birch shaft with numerous wraps of sinew. Three feathers found nearby were used to fletch the arrow. While these feathers could not be identified, Shúhtaot’ine elders related that eagle, owl, duck and goose feathers were used for fletching. Like the bow, this arrow is more than 400 years old.

Stone Knife

This beautiful, finely made tool was carefully chipped by a skilled toolmaker. It is made from grey-blue chert, a stone similar to flint. Note how the flakes are evenly spaced and chipped across the surface of the tool at the same angle. Unfortunately, no organic material was found with the tool so it cannot be radiocarbon dated. However, similar tools with the same distinctive flaking pattern have been found in southern mountains and date to around 10,000 years old.

Based on the size and shape of the tool, it is likely that it is a knife and may have been used to butcher caribou killed at the ice patch. Such a finely made tool would have been missed when it was lost.

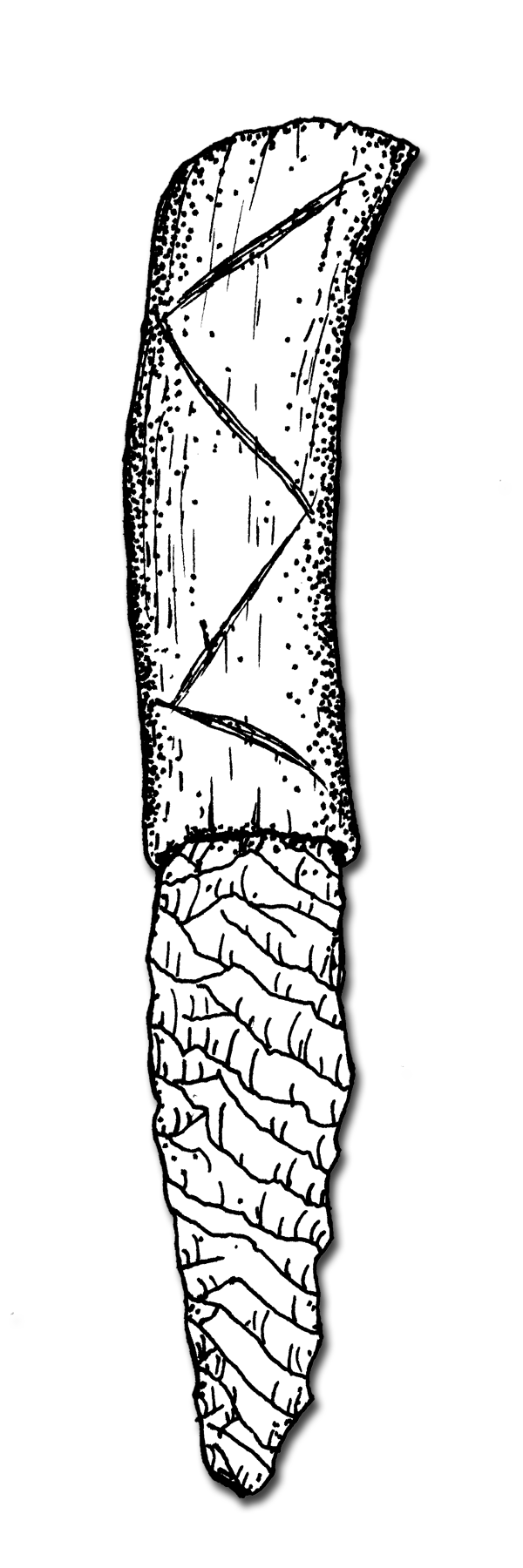

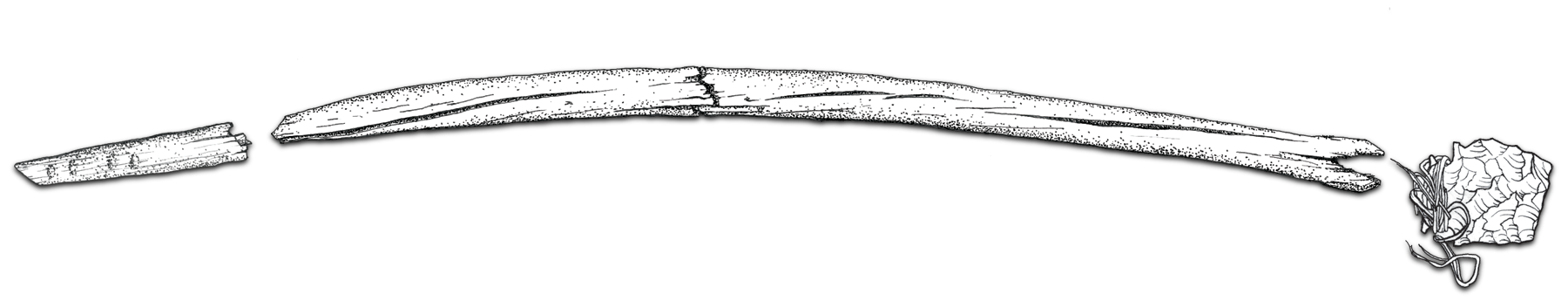

Throwing Dart

Throwing dart segments we found

A foreshaft, made from wood from Saskatoon berry cane, was found with its stone projectile point and a fragment of the birch shaft. The tip of the stone point was broken, but the sinew lashing was still wrapped around the point base. This suggests that a dart missed its target and hit the nearby rocks, breaking the point tip.

How the segments were assembled

For some reason the hunter didn’t retrieve his hunting tool. Perhaps, he fired another dart and, being successful, forgot about the miss. Radiocarbon dates indicate that these events occurred more than 2400 years ago. Throwing dart technology is very ancient and was used by hunter-gatherer societies around the world.

How to hold and throw a dart

Yamǫ̀zhah and the Evil Family

Shúhtagot’ine oral tradition tells a story of an important cultural hero named Yamǫ̀zhah, who is known throughout the north for making the laws that the Dene live by today.

In one of the stories, Yamǫ̀zhah encounters an evil family who wants to kill him. They fool him into thinking that their daughter would make a good wife for him. The father then sends him on a series of perilous journeys to collect the various materials needed to make arrows, including Saskatoon berry canes.

However, at each place, Yamǫ̀zhah encounters a dangerous monster. To collect the materials, he must kill the monsters. Though he successfully returns with all the material required to make arrows, he realizes that the family is evil. He manages to kill them before they can hurt others.

Science

on ice

Stories in the ice and dung

A grain of pollen from an Artemisia plant, a hardy shrub found in a dung layer dating to 1700 years ago. (photo: PWNHC)

The layers of caribou dung in the ice patches are of great value to scientists who study changes in caribou diet and disease. Climate and vegetation patterns in the area can be studied over long time spans. Pollen and plant fragments trapped in the caribou dung tell us what caribou were eating and what kinds of plants were present in the region over the past 5000 years. Insect parts trapped in the dung also tell us about what the local environment was like in the past. Ancient DNA extracted from caribou bones found near ice patches help us to understand changes in caribou populations over time.

These studies show that the environment has changed little over the last 5000 years, until recently. So far, the Redstone caribou population has remained stable over this time span. What kinds of environmental changes can we expect as the global climate continues to warm?

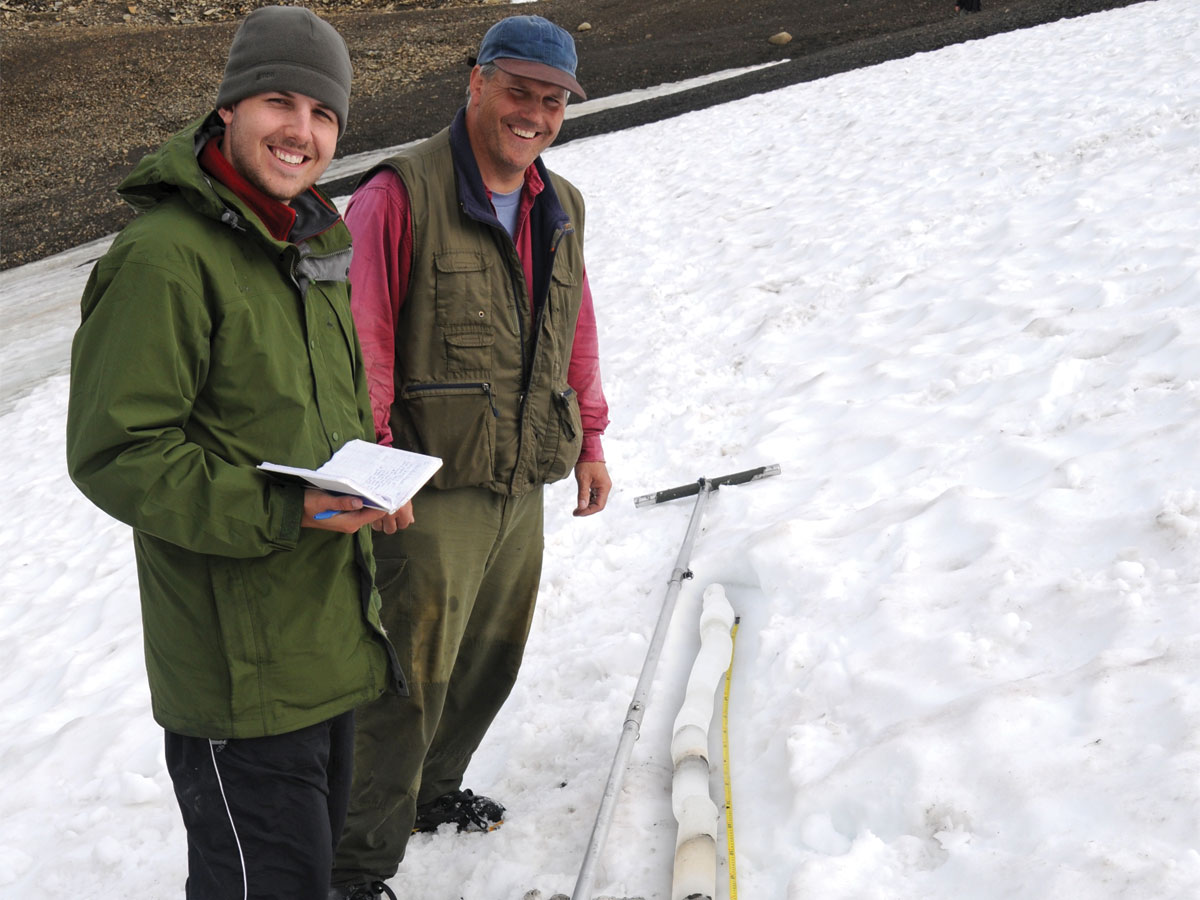

Poopsicle

If you sliced through an ice patch you would see layers of frozen caribou dung separated by layers of clean ice. Ground-penetrating radar and ice coring enable us to peer into the interior of the patches. The largest ice patches have as many as eight layers of caribou dung separated by ice.

We use a technique called radiocarbon dating to determine the age of each caribou dung layer. As the core below shows, the caribou dung at the bottom of the patch is the oldest. The ice cores show us that mountain caribou have used the ice patches for over 5000 years.

Time is running out …

Recent global climate change is causing the frozen parts of the Earth – its cryosphere – to melt rapidly. As sea ice melts, ocean levels rise. When permafrost melts, riverbanks and lakeshores collapse. As a result, archaeological resources are increasingly put at risk. Heritage resources in the Northwest Territories are particularly vulnerable because of our lengthy coastlines and vast areas of permafrost. Ice patches are melting after being relatively stable for 5000 years. Archaeologists are working to try to rescue the artifacts as they melt from the ice, but we all need to take steps to slow or stop global warming.

A cross-section shows the relationship between the increase of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere and the melting of ice patches

Acknowledgements

This project represents over five years of research carried out by the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre in partnership with the Tulita Dene Band and many talented scientists. Funding was provided by Canada's commitment to International Polar Year and continues with the logistical support of the Polar Continental Shelf Project.

|

|

|

|

For the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre

Text and subject content by Tom Andrews & Glen MacKay

Artwork by Rae Braden • Graphic Design by Dot VanVliet • Web Design by Rajiv Rawat