|

Northern Vignettes

Arctic Harpoons

Beechey Island

Crystal II

Deline/Fort Franklin

Fort Hope

Fox Moth

Kellet's Storehouse

Naujan

Old Fort Providence

Old Fort Reliance

Stone Church

Thule Village

Yellowknife

Fort Journal

|

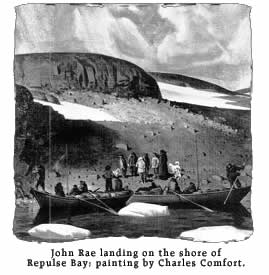

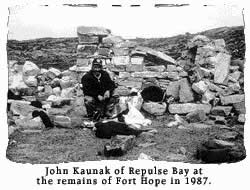

Fort Hope, located on the North Pole River flowing into Repulse Bay, near a place now called Neakongut, was the winter quarters of Dr. John Rae (1813-93) of the Hudson's Bay Company and ten men of the Arctic Expedition of 1846-47. A stone house, four houses made of snow blocks, and two observatories comprised the original camp. The snow houses with skin roofs held provisions, fuel, meat, and baggage and were connected by passages under the snow while the observatories, built of snow with a pillar of ice in each, were used to study the aurora borealis and magnetic fields.

Charged with exploring the coastline between Fury and Hecla Straits and the Boothia landmass, Rae's first Arctic expedition charted 1100 kilometres of coastline around Committee Bay, revealing that Boothia is a peninsula and that the Northwest Passage did not lie in this direction. On his fourth and last expedition to the Canadian

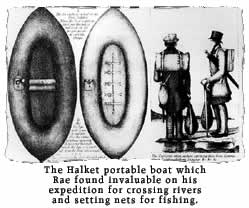

Arctic in 1853-54, Rae Covering 21,000 kilometres, often on foot and snow shoe, Rae mounted four expeditions into the Arctic, surveying over 2800 kilometres of coastline previously uncharted by Europeans. He is respected for his ability to travel rapidly and lightly by supporting his party on the resources of the land and using Inuit ways.

Rae's observations of natural phenomena are also keen. At Repulse Bay, he watched the smaller kind of seal (P. vitulina) " ... whilst the ice is forming, keeping breathing holes open ... by popping up their heads, and then throwing the water and broken ice on the surface of the flow with their 'flippers', where it freezes, and thus makes the ice after a time much thicker round the edge of the hole than elsewhere ... The advantage to the seal of the ice thus thickened ... is that, when the first fall of snow takes place, however slight, it drifts over and covers the opening ... and acts the double part of concealing him from his enemies and of preventing the cold from freezing the opening..." (Cooke 1968:175)

Historical and archaeological remains are protected from any disturbance by the Northwest Territories Archaeological Sites Regulations. Removing artifacts or altering structures destroys unique information from the past. References Cooke, Alan. "The Autobiography of Dr. John Rae (1813-93): A Preliminary Note." The Polar Record, Vol 14, No. 89, pp. 173-177, 1968. Houston, C. Stuart. "Dr. John Rae: The Most Efficient Arctic Explorer." Annals RCPSC, Vol 20, No. 3, pp. 225-228, May 1987. Newman, Peter C. "The Arctic Fox". Equinox, No. 23, September/October 1985. Rae, John. Narrative of an Expedition to the Shores of the Arctic Sea in 1846 and 1847. Canadiana House, 1970 Rich, E. E. and A. M. Johnson, Editors. John Rae's Arctic Correspondence with the Hudson's Bay Company on Arctic Exploration 1844-1855. London: The Hudson's Bay Record Society, 1953. Richards, Robert L. Dr. John Rae. Caedmon of Whitby, 1985. |

The walls of the stone house were two feet thick, with three glass

windows. Caribou skins stretched over a frame of wood furnished

the door, and a roof was fashioned with the oars and masts of Rae's

boats, the Magnet and North Pole, and covered with oilcloth and

moose hide. The house proved to be cold with daily indoor temperatures

of -25 C. Despite the weather, the party celebrated Christmas of

1846 with a dinner of "excellent venison and a plum pudding,"

brandy punch, and a game of football. On his next stay at Repulse

Bay in 1853-54, Rae preferred to live in a snow house less than

one kilometre south of Fort Hope.

The walls of the stone house were two feet thick, with three glass

windows. Caribou skins stretched over a frame of wood furnished

the door, and a roof was fashioned with the oars and masts of Rae's

boats, the Magnet and North Pole, and covered with oilcloth and

moose hide. The house proved to be cold with daily indoor temperatures

of -25 C. Despite the weather, the party celebrated Christmas of

1846 with a dinner of "excellent venison and a plum pudding,"

brandy punch, and a game of football. On his next stay at Repulse

Bay in 1853-54, Rae preferred to live in a snow house less than

one kilometre south of Fort Hope.  returned to Fort Hope and described it in his journal.

returned to Fort Hope and described it in his journal. "My

party have twice wintered without fuel, except for cooking,--once

in a stone house, and once in snow huts; having carried an inadequate

supply of provisions, we obtained by our own exertions, food for

twenty-two months of the twenty-seven we were absent, fully two-fifths

of which ... was killed by myself ... By following the native custom

of using snow houses (which I learnt and caused my men to learn

how to build) to rest in during our spring journeys, the weight

we had to haul was considerably reduced. The bedding for myself

and four men amounted to 24 lbs. ... The bedding...of Captain S.

Osborne's party of eight in spring, 1853, amounted to [140] lbs.

weight..." (Rae in Richards 1985:185)

"My

party have twice wintered without fuel, except for cooking,--once

in a stone house, and once in snow huts; having carried an inadequate

supply of provisions, we obtained by our own exertions, food for

twenty-two months of the twenty-seven we were absent, fully two-fifths

of which ... was killed by myself ... By following the native custom

of using snow houses (which I learnt and caused my men to learn

how to build) to rest in during our spring journeys, the weight

we had to haul was considerably reduced. The bedding for myself

and four men amounted to 24 lbs. ... The bedding...of Captain S.

Osborne's party of eight in spring, 1853, amounted to [140] lbs.

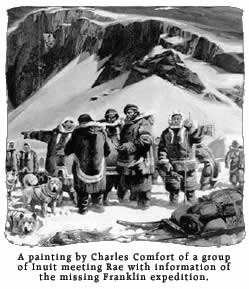

weight..." (Rae in Richards 1985:185) On his last foray of 1853-54, Rae learned of the deaths of the members

of Sir John Franklin's expedition of 1845 from In-nook- poo-zhee-jook,

an Inuk, and purchased 45 relics which had belonged to the Europeans.

For recovering and returning this information to Britain, Rae was

awarded the Admiralty's prize of £10,000. His news that Franklin's

men had resorted to cannibalism so affronted Britons' sensitivities

that controversy raged and Lady Jane Franklin opposed the awarding

of the Admiralty's prize to Rae. These Franklin relics are now in

the Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh.

On his last foray of 1853-54, Rae learned of the deaths of the members

of Sir John Franklin's expedition of 1845 from In-nook- poo-zhee-jook,

an Inuk, and purchased 45 relics which had belonged to the Europeans.

For recovering and returning this information to Britain, Rae was

awarded the Admiralty's prize of £10,000. His news that Franklin's

men had resorted to cannibalism so affronted Britons' sensitivities

that controversy raged and Lady Jane Franklin opposed the awarding

of the Admiralty's prize to Rae. These Franklin relics are now in

the Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh.