The introduction of law enforcement in the North was part of colonial expansion, as Canada extended sovereignty over land and people.

When the police came north in the early 1890s, they lacked the skills and knowledge necessary to survive the harsh northern climate. Indigenous languages, cultures, and ways of life were completely unfamiliar to them.

Mounted police with S/Cst. Louis Cardinal (centre, back) and Chief Julius of the Teet’it Gwich’in (far right), Fort McPherson, 1904. HBC Archives/Provincial Archives of Manitoba – 363-R-34/3

Some would have froze because they didn’t know what kind of wood to use. What kind of footwear, direction of winds, hills and mountains and where to camp.

Winston Moses, son of S/Cst. John Moses, speaking about the RCMP

S/Cst. Andrew Stewart, S/Cst. Alfred Kendi with Inspector Nordie Kirk and Cst. Rolly Stewart, Richardson Mountains near Aklavik, 1946.

NWT Archives/N-2005-001:0120

Odillia Coyen making dry fish for winter patrol with S/Cst. Andre Jerome (right), Arctic Red River [Tsiigehtchic], 1957.

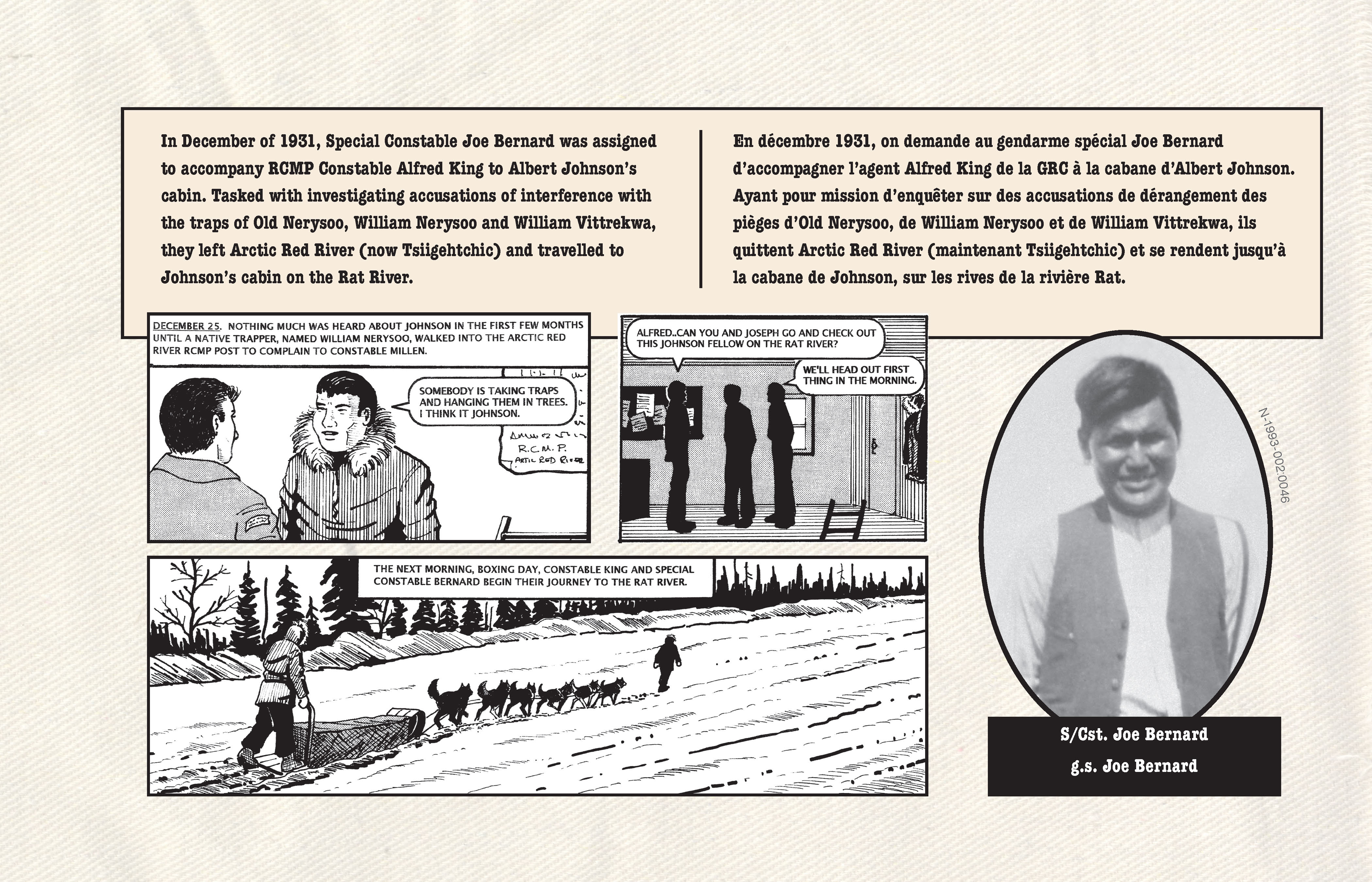

NWT Archives/N-1993-002:0046

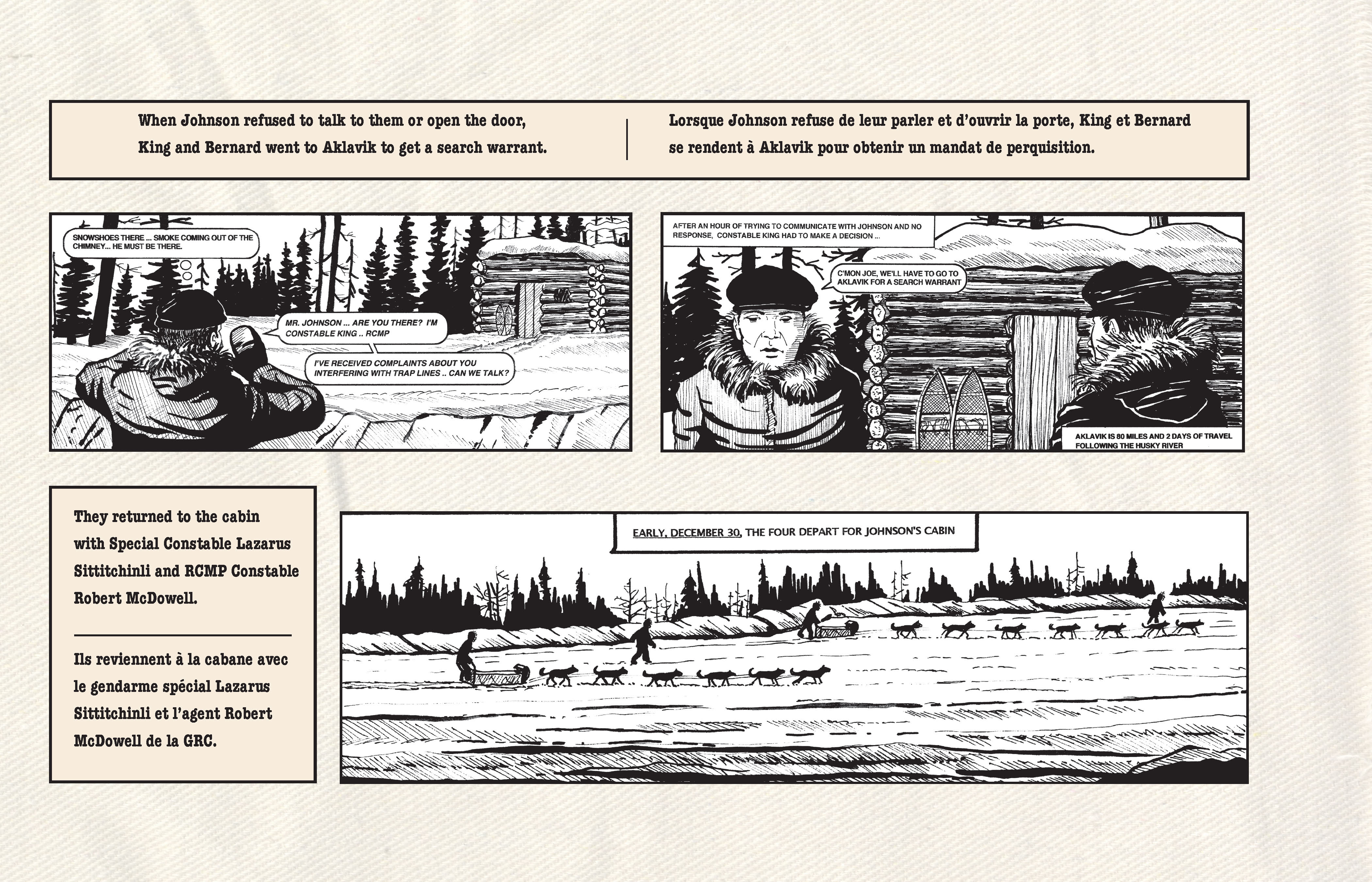

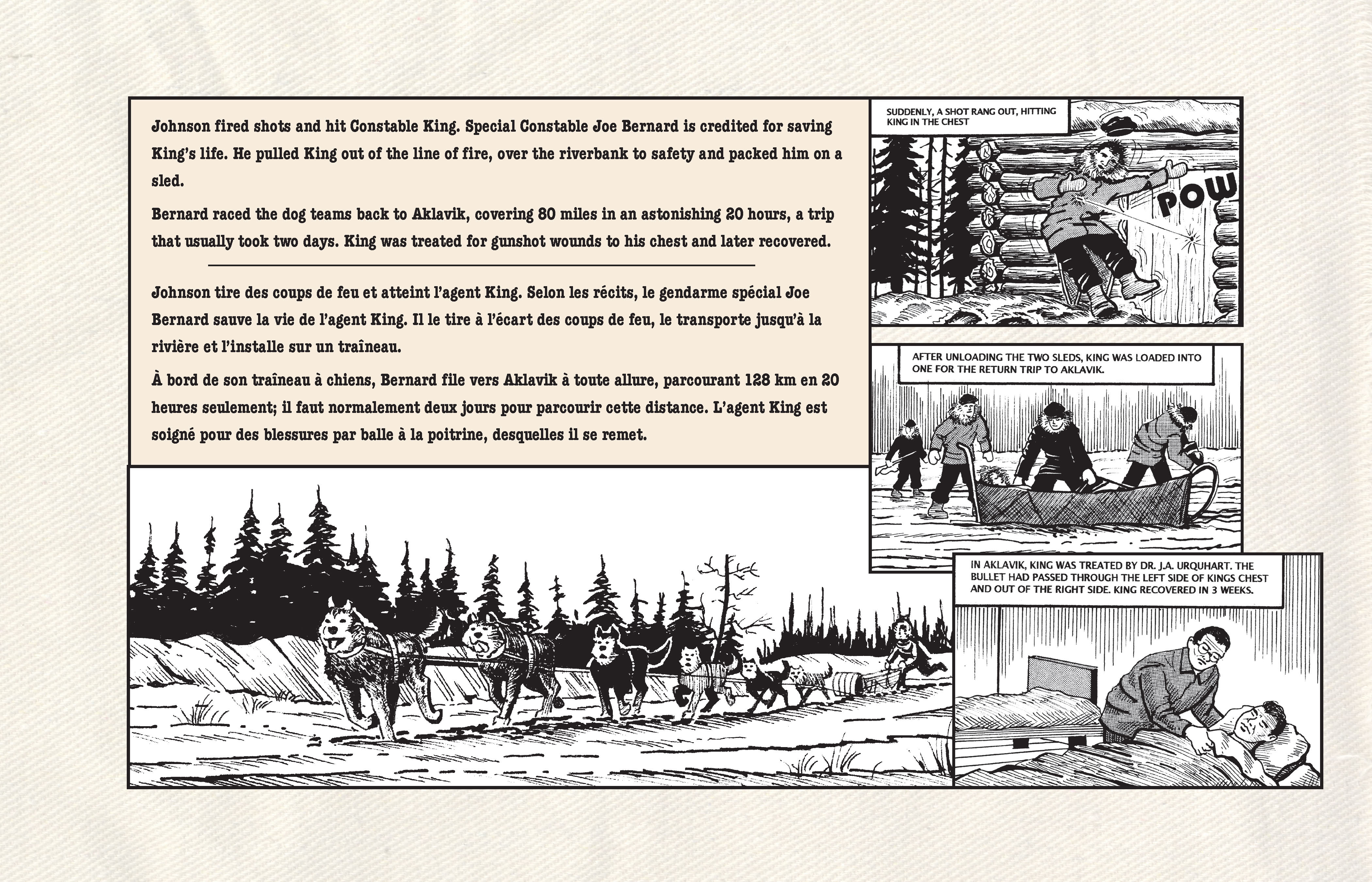

Most Special Constables were Indigenous people hired to help the police by teaching them how to survive in the north. Local women and families also provided essential support.

Special Constables worked alongside the police to help them understand Indigenous cultures and traditions. They helped break down barriers and built a cultural bridge between government and the people.

Special Constables are credited with creating positive relationships between the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and communities.

S/Cst. Otto Binder Jr. (centre) with Insp. W.G. Fraser and unidentified RCMP constable, 1957. NWT Archives/N-1990-005:0014